Workplace Adaptation in Times of Crisis – Resiliency in the Face of Chaos

I was in Houston during Hurricane Harvey and I am still here; Houston is my home. I was lucky. I did not lose my home, car or office to flooding or end up in knee deep water, but many did:

►1) over 50 inches of rain fell;

►2) over 94,000 structures were damaged;

►3) 35,000 people were in 240 shelters;

►4) in one area alone (Harris County) 40% of all the buildings flooded were in “minimal flood hazard” zones; and

►5) 450,000 people needed emergency assistance. (See www.nytimes.com/interactive/)

The cascading health effects of debris, sewage, mold and unidentified bacteria in displaced water will take a while to determine.

Harvey gave me pause for reflection. It was a wake-up call, for me and others who design the workplace as well as for our clients. We now realize, through our own design experiences, that employer operations and employee wellbeing are closely interwoven. Accordingly, it is incumbent upon those of us in the design profession to better understand corporate and professional worker resiliency in the aftermath of critical incidences such as hurricanes, fires, political events and economic changes affecting organizations and individuals.

If natural disasters find us in uncharted territory when it comes to getting people back to work, this is because, to a large extent, low-probability, high-impact events invite us to “kick the can down the road,” especially in the face of the exhaustive of recovery.

This is not to make light of the personal losses or tragic circumstances many organizations and office workers face. But, through our professional experience and responsibilities, we must explore systemic designs to mitigate the damage, promote organizational resilience and support the resilience and recovery of employees, just as others are addressing the needs of local governments and their residents.

This discussion is not about remote working and readiness before disruption and crisis. There are many articles on business continuity, working from home, economics of reduced revenue, lost productivity and preparing in advance. (see fmlink.com/articles/5-ways) We are exploring resiliency during the aftermath. In particular, we are examining the extent to which organizational resilience promotes, and is dependent upon, the resilience of its individual employees.

From this perspective, we ask, “What does it take for a service/professional/office organization to be built for resilience?” In many respects, we must take into consideration the same factors involved when significant organizational change is underway. As we have learned, successful change management is built upon an organization’s social dynamics and the collective, rather than solely focused on the individual. You need the organization and the individual employees to work in concert. Organizations want to be as flexible and agile as their employees in times of change and crisis.

There are five scenarios that corporate and professional workers might face in a natural disaster, and we saw them in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey:

There are five scenarios that corporate and professional workers might face in a natural disaster, and we saw them in Houston in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey:

►1) you could go back to your place of work yet the displacement due to the flooding and destruction affecting people’s personal lives made it difficult to concentrate on work,

►2) you might not be able to get back to your workplace because it was inaccessible due to impassable roadways and bridges,

►3) for others, their workplace was either partially or totally damaged so making their way to their workplace was not possible,

► 4) temporary living quarters or personal residences were damaged so other arrangements had to be made, some people ended up in nearby shelters, and

►5) there were others who were out of town during the storm without a way to get back to Houston due to closed airports or other transportation options being unavailable.

The organization can help develop individual resilience by developing its own resilience in a manner that mitigates the stress on its individual employees. What the individual desires is organizational reassurance that they are not alone and to understand what the new normal is with respect to their organization. The question for the organization is how can it support individual resilience. This requires a strategy based on sound evidence both quantitative and qualitative. Research by Professor Alan Hedge of Cornell University describes four common characteristics of resilient workers; these identify the areas in which an organization can support its workers. In summary, resilient workers: ►1) bounce back from defeat and disaster,

The organization can help develop individual resilience by developing its own resilience in a manner that mitigates the stress on its individual employees. What the individual desires is organizational reassurance that they are not alone and to understand what the new normal is with respect to their organization. The question for the organization is how can it support individual resilience. This requires a strategy based on sound evidence both quantitative and qualitative. Research by Professor Alan Hedge of Cornell University describes four common characteristics of resilient workers; these identify the areas in which an organization can support its workers. In summary, resilient workers: ►1) bounce back from defeat and disaster,

►2) respond flexibly and adapt to changing circumstances,

►3) perform well under pressure, and

►4) don’t “sweat the small stuff”. Further, the more someone has been exposed to stress in the past, within limits, the greater their ability to weather stress in the future. In other words, organizational training on procedures to use during stressful or catastrophic situations can be the essential step, a sort of “Fire Drill,” if you will; this, of course, is what the military does as a matter of routine since their purpose is to deal with extraordinary, highly stressful situations.

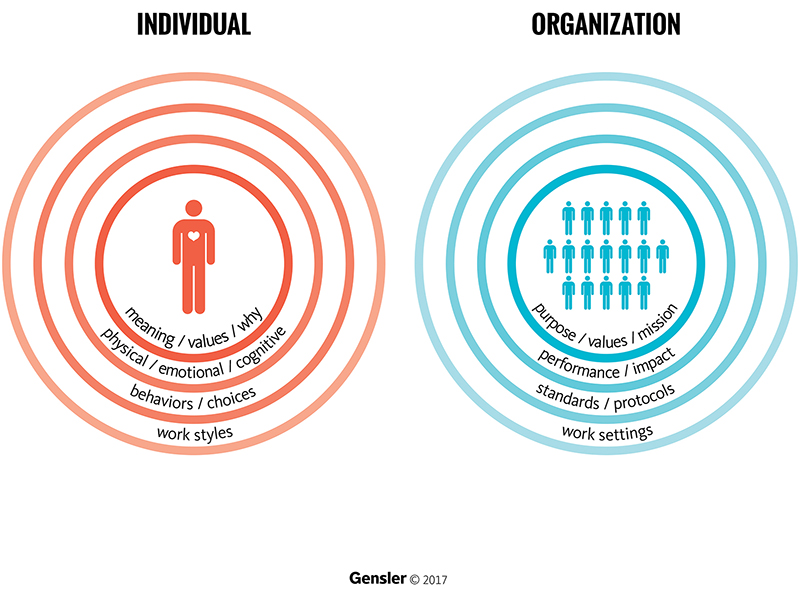

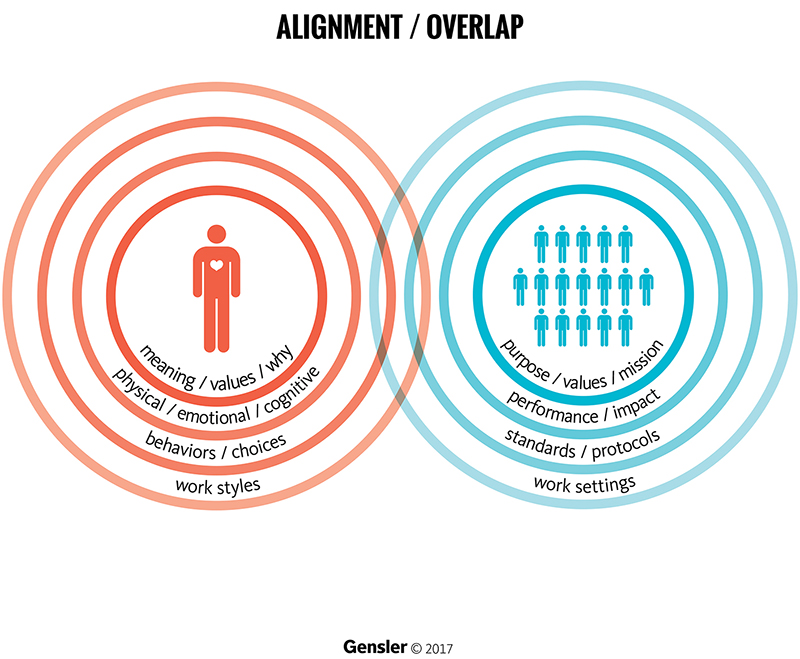

One barrier to progress, however, is the ostensible misalignment of organizational needs and those of individual employees. Organizations are typically designed to be stable over the long-term. They have policies, procedures and processes in place to build more stability and more consistency in executing processes and administering policies that make it more difficult for the organization to be agile, adaptable and resilient. This is changing for the corporate and professional worker though probably not as fast as the accelerating rate of change in crisis-driven current events.

One barrier to progress, however, is the ostensible misalignment of organizational needs and those of individual employees. Organizations are typically designed to be stable over the long-term. They have policies, procedures and processes in place to build more stability and more consistency in executing processes and administering policies that make it more difficult for the organization to be agile, adaptable and resilient. This is changing for the corporate and professional worker though probably not as fast as the accelerating rate of change in crisis-driven current events.

My suggestion is that, organizational resiliency may be more a factor of organizational design than the capacity of the individual to manage change in a crisis. Fortunately, we are seeing more companies embracing alternative work strategies and activity-based working provides a model for learning and growth for the individual and for the organization to be flexible, agile and resilient to changing conditions. Even organizations that are not built-for-change become quick learners in a crisis. You only have to look at the oil industry and the quickness with which they are embracing alternative ways of working and are supporting their employees after Harvey (see https://www.reuters.com/harvey-conocophillips/ and http://www.chron.com/business/energy/ )

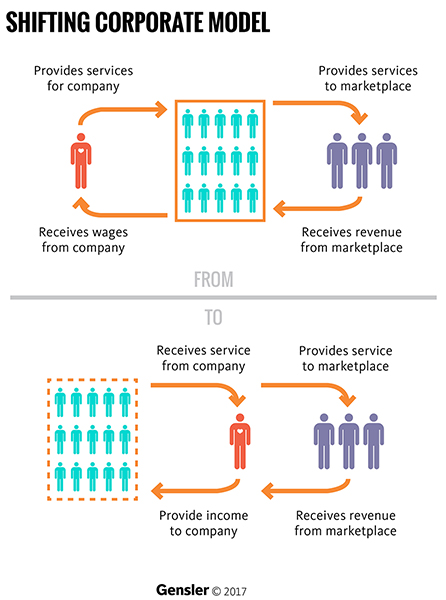

In the past, organizations were less inclined to consider their employees’ needs beyond their capacity to generate revenue. Today that has changed. Companies, particularly in the service economy, are dependent upon the creativity and productivity of employees for revenue production. While the company remains at the center of the business model, we now see the individual as the generator of the revenue that ensures the viability of the company. Companies must consider not only fair pay and well-being, but do more and more to acquire and maintain these essential organizational assets.

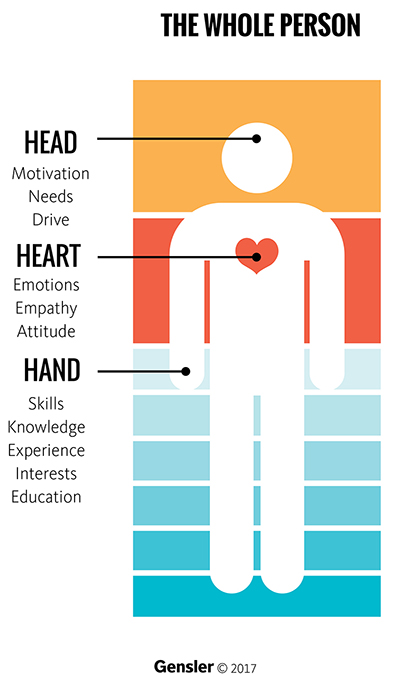

This is a huge shift in the value proposition for most companies. It is also why a corporate or professional worker today is accommodated more as a “whole person” than as an asset to be discarded when depleted. Companies may still hire for a strong resume and task expertise, but eventually new hires become part of the organizational culture and need support – especially during times of crisis. We cannot forget that every day the whole person shows up and in a crisis, there is a critical shift from accomplishing tasks to the emotions surrounding current events. Evidence supports that we feel before we think and generally don’t act until the head and heart are reconciled. In times of crisis, organizations need to better communicate, support workers in alternative work settings and find ways to improve business continuity. Action over analysis is critical when there is a major incident.

As designers, we have a responsibility to support employees and organizations, provide counsel as it relates to the workplace and offer strategies for how best to be resilient. This discussion was not intended to provide a solution. Solutions will come from each one of us as we confront our own resiliency in times of crisis and catastrophe. This is a complicated, personal journey and it would be difficult to predict how each of us will act in these situations. Our profession has trained us to look both at the big picture and at the immediate issues. This affords us an important vantage point and perspective to offer in times of turmoil. We need to take what we have learned and experienced in our work and make it applicable to helping others who are going through profound change brought on by crises.

As designers, we have a responsibility to support employees and organizations, provide counsel as it relates to the workplace and offer strategies for how best to be resilient. This discussion was not intended to provide a solution. Solutions will come from each one of us as we confront our own resiliency in times of crisis and catastrophe. This is a complicated, personal journey and it would be difficult to predict how each of us will act in these situations. Our profession has trained us to look both at the big picture and at the immediate issues. This affords us an important vantage point and perspective to offer in times of turmoil. We need to take what we have learned and experienced in our work and make it applicable to helping others who are going through profound change brought on by crises.

I believe that underlying our passion for design is a deep empathy for the people we serve, a capacity for invention in times of necessity and the ability to iterate solutions that do not lend themselves to linear processes. As designers, we can use our minds, our hearts and hands to support recovery efforts whether in the workplace or otherwise. We could all be more resilient and helpful in these times.

Sven Govaars is an organizational design and change strategist at Gensler creating highly productive work environments. He actively works with leaders facilitating transformation in their organizations. He is known for generating insights and amplifying the strength of high profile teams. Sven has a proven ability to solve complex problems using collaborative methodologies that inspire, teach, and inform successful outcomes. Go to Free Range Workspace for more on Sven’s work or to reach Sven email him at sven_govaars@gensler.com.