The Traceability of Wood

Do you know if the wood you work with is legal? Do you know where it comes from, and if it’s an endangered wood species? Is it from a high-risk region? Do you care?

A few weeks ago at the Living Product Expo, a conference in Pittsburgh that gathers sustainability experts together to learn about the newest innovations in sustainable products and materials, a session called “Traceability of Wood: Challenges and Opportunities for Transparency in the Supply Chain” provided an in-depth look at something even many sustainability experts in the A&D field know little about.

The session, led by Mara Baum, AIA, LEED Fellow, WELL AP, Sustainable Design Leader, HOK; Paul Davis, LEED AP BD+C, FSC® Multisite Manager, Columbia Forest Products; and Ruth Nogueron, Associate, World Resources Institute, discussed the impact of illegal forestry practices, the risks it brings to living buildings and products, a brief overview of the laws currently in place to prevent illicit activity, and wood traceability tools and resources that designers/architects can use to research wood and learn more.

“The reason I got involved in learning about this is because I was heavily involved in the development of the LEED rating system,” said Ms. Baum, in an interview following the session.

She notes that the USGBC began to make changes for less stringent requirements around wood.

“I think many designers and the public think that because we’re working in the U.S. and our legal system is well developed, nothing illegal is going on. But illegal wood is alive and well in the United States. The question becomes, ‘Whose job is it to be a leader in that area?’

“I realized there was a lot I didn’t know, and so I started calling people up in the industry and asking questions, and talking to the USGBC about it. As a design community, we’re really just beginning to understand that this is a huge issue.”

Here’s a peak into some of the activity in illegal timber trade and use:

>Use of wood species that are protected by national or international law

>More timber than authorized is extracted, or it’s extracted outside permitted areas

>Over-scaled tracts, logs (documenting more wood than there really is) with laundered, illegal wood introduced later in supply chain to make up the difference

>Harvested where royalties, taxes, and fees on harvest are evaded

>Harvested in violation of detailed regulations, contract obligations required to protect citizens, environment

>Timber illegally exported in contravention of national law

>Timber transported at night in violation of curfew designed to combat illegal timber trafficking

>Timber that is mis-classified, falsely declared or transferred with corrupt pricing schemes

There are a number of compelling reasons for stopping illegal logging, among them:

>Legal operators are disadvantaged

>Depression of timber prices globally

>Deprives governments, communities of shared revenue

>Funds criminal enterprise

>Undermines rule of law and sustainable forest management

>Habitat, forest and watershed destruction

>It’s against the law!

Do you know what kind of wood you’re specifying/using? In the following list, at-risk wood species are highlighted in red:

Afrormosia/African Teak

Anigre

Ajo

Almendro

Argentine Lignum Vitae

Tamo Ash

Black Ebony/Gabon Ebony

Bois de Rose

Brazilwood

Ipe/Brazilian Walnut

Spanish Cedar

Cocobolo

Iroko

Lauan

Madagascar Ebony

Lignum Vitae

Mahogany (Cuban, Honduran, Mexican)

Monkey Puzzle

Ramin

Japanese Oak

Black Pine Podocarp

Rosewood (Brazilian, Honduran, Yucatan, Siamese)

Satinwood

Wenge

Zebrawood

Zitan

Forestry regulation is anything but cut-and-dry, though. There are different methods of categorizing wood that, while necessary, complicate the issue.

While “legal wood” is just that – wood that is not endangered, mis-classified, illegally harvested or traded, etc., there is something called “FSC controlled wood.” The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) is a nonprofit that sets the standards for what is a responsibly managed forest, and is a leading voice in the forestry industry. Its “FSC controlled wood” is material from acceptable sources that can be mixed with FSC-certified material in products that carry the FSC Mix label. Controlled wood meets the requirements of the two main FSC controlled wood standards.

“Controlled wood is not FSC wood, but it’s still ‘controlled’ by the FSC,” said Ms. Baum. “It’s the baseline for what is acceptable.

The main law addressing wood in the U.S. is called the Lacey Act; here are the basics:

>Prohibits trade in illegally sourced wood, making it unlawful to import, export, transport, sell, receive, acquire or purchase any plant (including wood) that was taken in violation of law (in country of harvest).

>Requires Declaration: The importer of record must file declaration document for imports containing scientific name of plant material, country of harvest, value of the plant and quantity of the plant.

>Establishes penalties for violating the law in country of harvest. These penalties can include: seizure by U.S. Customs, forfeiture, and civil penalties such as fines, possible imprisonment, and felony prosecution.

And addition to the Lacey Act, there are other laws and policy agreements in place around the globe. But these laws and agreements require a lot of effort and funding.

“The Lacey Act is an annual fight to keep the bill going,” said Mr. Davis. “It takes a lot to fund it, and an intense understanding of the different players, the supply chains and how everything works.”

But Ms. Baum says she sees a potential for change.

“The forestry industry is a supertanker; it’s not going to change easily,” said Ms. Baum. “But it can happen with lots of smaller steps and with patience. Right now it’s not even on the minds of most people in the sustainability industry. It really feels like a whole entire new issue that hasn’t been touched.”

Traceability is helpful for a few reasons:

>To assess claims associated with the product. Was the wood legally harvested? Were the forests sustainably managed? Did local communities benefit from the forest management activity?

>To ensure you’re getting what you pay for and protect against fraud.

>To manage product quality.

But how much traceability is enough? Wood is a part of so many products and industries, and those industries all operate differently in their relationship with wood. It’s a complicated landscape.

Technology is being applied to innovation in shedding light on and preventing illicit wood activity, and while not perfect, there are some excellent tools at work, including:

Resources for learning more:

>Forest Legality Initiative – www.forestlegality.org

>Sustainable Procurement Guide – www.sustainableforestproducts.org

>WRI’s Legality Guide – http://www.wri.org/publication/sourcing-legally-produced-wood-guide-businesses

>Illegal Logging Portal – https://www.illegal-logging.info/

>Nepcon’s Sourcing Hub –http://beta.nepcon.org/sourcinghub/timber

So, do you care? The session leaders noted a study that found that all designers say they don’t want to use endangered wood species, but 99% don’t know which species are endangered, and 40% say they would still specify an endangered wood if a client wanted it.

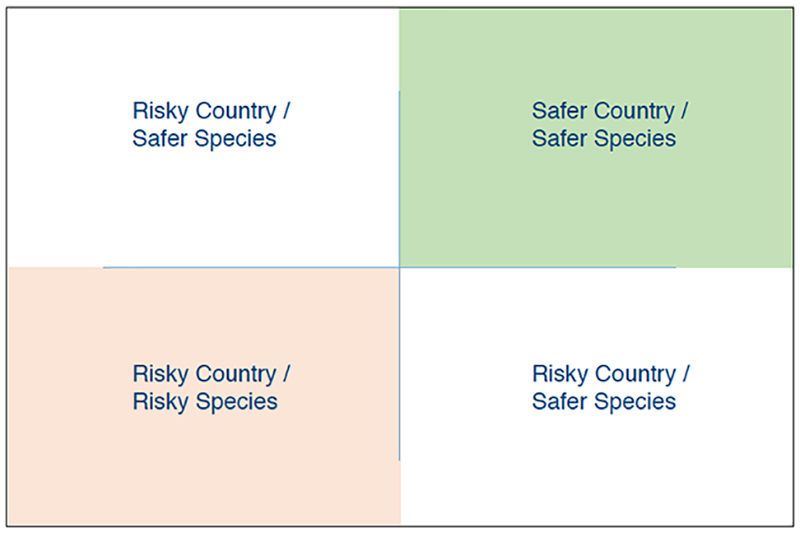

There are opportunities for design and construction teams to reduce the risk of use of illegal wood in their projects. Aside from learning the ins and outs of wood traceability issues, getting into the habit of asking about the wood they’re specifying is a good start.

“The easy answer is to specify as much FSC wood as possible,” said Ms. Baum. “That won’t be possible with every single project, but it’s a goal. An architect or designer or owner may not have a legal issue right now if they accidentally specify endangered or illegal wood, but there is a reputation issue. If people become more in tune to it, then it could affect their reputation significantly.

“Just because it’s traceable and legal, doesn’t mean it’s sustainable in the way that it should be,” said Ms. Baum. “Designers can benefit from establishing an intellectual and personal interest in what’s growing nearby; but that also suggests that the U.S. is the end-all, be-all best for every project, and sometimes it’s not. Manufacturers who are concerned with internally managing risk will hopefully begin to self-regulate so they can offer that point to designers. It’s very aspirational; it’s not a comfortable place to be all the time.”