Trade Tariffs: Impact on the Contract Furniture Industry

Before I address the likely effect of the Trump Tariffs on the workplace design and furnishings industries, I think it is worthwhile to talk about tariffs in general – their history and background.

Before I address the likely effect of the Trump Tariffs on the workplace design and furnishings industries, I think it is worthwhile to talk about tariffs in general – their history and background.

Tariffs are one of the oldest tools a government can use to regulate trade with other countries. They are simply taxes on goods flowing into a country from another country. Historically, the main objectives of tariffs were to raise revenue and protect the country’s supply of gold and silver, since international trade was nearly always paid with one or the other of those precious metals. But there has often also been a less obvious xenophobic underlying motivation.

In the 16thcentury both China and Japan famously “closed” their borders to trade – hitting foreigners with high tariffs and extremely restrictive travel policies.

In China the emperor restricted access by not allowing westerners to travel beyond a specific city: Guangzhou.

Japan went even further. In the 15thcentury Japanese trade with the rest of the world was restricted to only the Chinese and Portuguese and only at Nagasaki. However, the Portuguese ran afoul of the Japanese rulers by rather successfully trying to convert people to Christianity, so they were expelled and replaced by the Dutch. In both China and Japan, the penalty for a westerner caught outside the trading zone was death.

These trade policies remained in effect until the middle of the 19thcentury. Between 1839 and 1860, the British, with some help from other western countries, defeated the Chinese in two “Opium Wars.” This resulted in the establishment of trading ports along the coast of China, granting access to Chinese markets for most European countries and America.

Similarly, in 1853 our own Admiral Perry “opened” Japan to trade using the threat of force, known as “gunboat diplomacy,” to convince the Shogun and Emperor that it would be wiser to trade than to fight.

Nevertheless, throughout most of history the main purpose of tariffs has been a way for a country to raise money – all the while protecting its gold and silver reserves. In fact, until 1916 when the United States ratified the 16thAmendment, formally creating the income tax, tariffs were the main source of U.S. government revenue.

But in recent times the main purpose of tariffs is more often about protecting specific domestic producers from foreign competition, or as in the case of Trump’s Tariffs, about using tariffs as a weapon to “squeeze” trade concessions from countries perceived as harboring unfair trade policies in their trade relations with the United States.

The problem with tariffs used as bargaining chips is that they have been shown over a very long history to produce unintended negative consequences in the country deploying them. As early as the very birth of our nation, with the publication of his landmark, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith identified consumption rather than production as the key to economic growth and the problem with tariffs is that they invariably lead to higher prices to consumers and a predictable drag on economic growth.

But we needn’t go back to 1776 for examples of the impact of tariffs. In commenting on the current tariffs, Republican Senator Orrin Hatch recently pointed out that, “Tariffs on steel and aluminum imports are a tax hike on Americans and will have damaging consequences for consumers, manufacturers and workers.”

As proof of this point we can look at the Bush tariffs of 2002, when his administration felt duty bound to try to protect the failing U.S. steel industry from foreign competition. The result of Bush’s tariffs was a $30 million hit to the economy, according to a lengthy government report from the U.S. International Trade Commission in 2003. Studies by outside groups conclude that the United States lost jobs because of the move: the employment gains in factories that make raw steel were outweighed by job losses in other industries, especially at companies that take raw steel and make it into parts for cars and appliances. To put it another way, it cost about $400,000 per job saved in the steel industry, according to an estimate by the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

According to an article in the Washington Post (read here), “The root of the current trade mess lies in a surplus of global steel, which most analysts blame on excess Chinese investment in steel production facilities.

Steelmakers worldwide produce 700 million tons of steel more than customers need, or seven times total U.S. production, the Commerce Department says.

That flood of steel has depressed prices, making it difficult for many American steelmakers to compete. Last year, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross negotiated voluntary reductions in global capacity. But Trump rejected the deal.

Trump had announced the tariffs in March but gave several U.S. allies temporary exemptions while they negotiated potential limits on shipments to the United States. At the time, the nonpartisan Trade Partnership estimated that the tariffs would cost five jobs for every position saved in the steel and aluminum industries.

“This is dumb. Europe, Canada and Mexico are not China, and you don’t treat allies the same way you treat opponents,” Sen. Ben Sasse (R-Neb.) said. “We’ve been down this road before – blanket protectionism is a big part of why America had a Great Depression. ‘Make America Great Again’ shouldn’t mean ‘Make America 1929 Again.’ ”

So it suffices to say that using tariffs as a means of “negotiating” trade deals is highly risky. What are the risks to our industry?

The first round of tariffs that went into effect in July were 25% on steel and 10% on aluminum, both key materials in office furniture. As costs increase one of two things happens: either prices rise – usually leading to softening of demand, or profits suffer – usually leading to layoffs. Nevertheless, the percentage of imported steel and aluminum as a cost factor to U.S. furniture manufacturers would probably not cause an undo amount of pain.

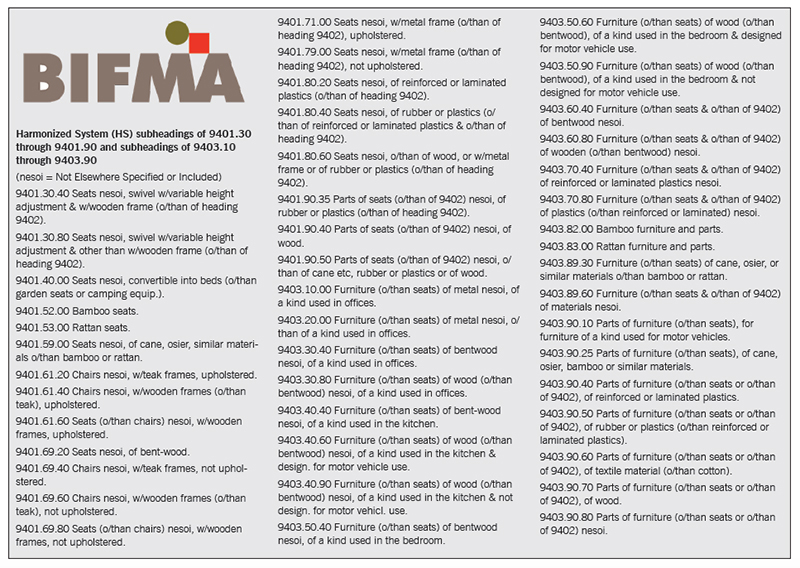

But the 2ndround of “proposed” tariffs is much more specific with its Harmonized System subheadings and this round calls out very specific component parts used extensively in the manufacture of office furniture.

But the 2ndround of “proposed” tariffs is much more specific with its Harmonized System subheadings and this round calls out very specific component parts used extensively in the manufacture of office furniture.

BIFMA joined other interested parties in weighing-in on the inadvisability of this escalation of what is already a Trade War. In its press release BIFMA framed the impact this way, “Furniture manufacturers are concerned and project that an increased cost in materials will have a negative impact on market demand, likely leading to a net job loss in this sector. Commercial furniture manufacturing in the United States is conducted in 48 states, driving an economic impact of nearly 15 billion dollars annually and spurring significant annual exports of 725 million dollars. (BIFMA Press Release)

In his official letter to the U.S. Trade Representative, BIFMA Executive Director, Tom Reardon said, “We project the increased materials cost will have a negative impact on market demand, likely leading to a net job loss in this sector. Commercial furniture manufacturing in the United States is conducted in 48 states, primarily Michigan, Indiana, California, Wisconsin, North Carolina, Texas, Pennsylvania, New York, Iowa, and Ohio.

Foreign competitors who source component parts from China would not see price increases from tariffs like U.S. manufacturers would. Thus, when they (Canadian, Mexican and European manufacturers specifically) export finished goods to the U.S., their cost basis would be more competitive than domestic U.S. manufacturers. This, coupled with the strong U.S. dollar would put foreign manufacturers in a very advantageous position in the U.S. market.”

While the administration allowed for extensive public comments, most of which argued against the tariffs, and no finaldecision has been made, nearly everybody assumes Trump has made up his mind.

Impacts will vary by company. Most of the biggest companies in our industry own plants and manufacture in China, but some also have plants in other low-cost-labor countries such as Thailand, Malaysia, and Viet Nam.

Many of the mid-sized to smaller companies rely heavily on parts and finished goods from China.

One thing is certain: it takes time to make changes to one’s supply chain, so the impact on the industry will vary depending on how long the trade war rages. It could cause a momentary negative dip in profits, or hefty increases in prices or lay-offs across the industry. We all will be watching with keen self-interest.