The Sustainable House: Architects At Work

As designers and architects, we know that designing for ourselves is not for the faint hearted but can be incredibly rewarding. Because we are gluttons for this kind of punishment, my husband Bob (who is also an architect) and I have designed a new home for ourselves every five or six years or so; I get restless, and whenever someplace needs a paint job, I say, “Time to move!

This time around, we decided to build something in the Tahoe area, where we have lots of family and where we have vacationed for years.

We wanted to make it as sustainable as possible, close to net zero, without breaking the bank. I am not a specialist in sustainability, but I work at a firm (Perkins+Will) where it’s one of our core values. And so at least I knew where to look to learn what I needed to learn. We started searching for a lot, and at the same time we ordered a half dozen books on green residential construction. Yes, very old fashioned, hard copies, but there were some sections we referred back to over and over – and there is nothing like a book for that kind of reference material.

We found a beautiful lot after about a year of looking, on what appeared to be a fire sale (we made jokes that the owner had the Mafia after him because he wanted to close so quickly). It had an existing 1980s ranchburger on it and our first (bad) idea was to be really sustainable and renovate the existing house.

Some of the most interesting case studies in the books were of renovations, and the house was situated well; it was a simple rectangle with the long axis facing south to the view. Perfect! We went ahead and did a design and a set of drawings, and immediately broke one of the primary rules that we always gave to our clients: if you are going to renovate more than 50% of a structure or interior, then get out the sledge hammer and start over. We got pricing back from several contractors, and after we picked ourselves off the floor, we realized that we should just start from scratch and design a house the way we really wanted it.

Once that decision was made, we did another design and set of CDs (fortunately, the architects were working for free). Bob had decided that when we moved out to Reno near the house he would GC it himself in order to save money, but also so we had more control over the quality and the design. He knew this was going to have a huge learning curve – he had done some construction himself, but never for a totally freestanding building, not to mention one that was using sustainable best practices – but he was game.

We also decided not to use any certification system but to try to achieve as close to net zero as possible, being careful about toxic materials and finishes, and recycling waste.

We did solar shading studies using a Sketch-Up model and oriented the house similarly to the old one, with the long axis facing the view to the south. We positioned the large rooms with big openings to the south, and added an overhang that would shade the windows in the summer and allow the low winter sun to penetrate into the space. We extended the roof 12 feet to the west in a large covered porch, also to shade the late day sun from entering the space during the summer.

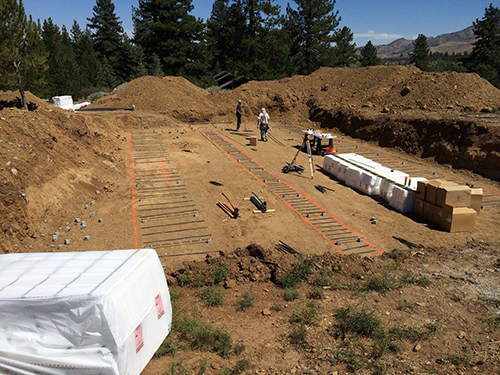

Bob also got interested (obsessed?) with a building system called ICF, or Insulated Concrete Forms, that could be used for foundations, walls and ceilings – even sloped roofs, if the pitch was not too steep.

The hollow Styrofoam forms stacked up like Legos, rebar got placed inside the hollow centers, and then the concrete was poured into the forms. The Styrofoam became the insulation, and then siding would get applied on the outside, and finishes on the inside. That allowed us to super-insulate the walls and ceilings; for the roof we added another 4” of rigid insulation on the outside. This also gave us a nice concrete floor that we could expose and polish, one that would absorb the heat from the low winter sun penetrating the space. We also put radiant heating in the floor.

We also decided to go with high performance windows with the glass “tuned” to the exposure, but not to invest in triple glazing.

We wanted the entire house to be concrete, even the large overhanging eaves, which we coffered to reduce weight and because we thought it would look cool. This became an exercise in insanity, because every one of the coffers had to have formwork fabricated out of millwork. There were 80 some odd little “sleds” made of plywood that had to be fabricated, set in place, and then removed. An entire network of scaffolding and catwalks had to be built around the perimeter of the house, and then taken down. The roof is beautiful, but we agree that there is a reason it is unique.

As the construction progressed, we learned the downside of all of these decisions when we wanted to change the bathtub in the master bath. We had a pretty good idea of where the tubing for the radiant heating was in the concrete and realized that we could not change the location of the drain in the original tub without risking hitting the tubing and cutting it.

So, some of our decisions were literally cast in stone; an all concrete house is just not the most flexible way to build. Once walls and roof were poured, moving or changing things was a bit of a challenge. However, we did know that it would never blow down, and it would also never burn down either. This did not stop the state of California from requiring that we fully sprinkler it.

At the beginning we decided to do full solar, and we got very excited when we learned about the new Tesla home battery, which we thought we could use to power the house at night or on cloudy days. However, we have since learned that the battery is discontinued, and we’ll have to come up with another solution for trying to be as much off the grid as possible. We also put in a geothermal ground loop connected to a heat pump, a feature that will reduce our heating needs in winter, and cooling (if needed, but unlikely because of the passive strategies we are using) in the summer.

The GC is slow, and the house is taking a while to complete, but he is very amenable to last minute changes!

We had planned on using a cementitious siding that comes in slats and has a naturally variegated texture similar to wood; but when we put the dark grey waterproofing on the outside of the house and it stopped looking like a large Styrofoam cooler, we realized we would prefer a monolithic look that would not compete with the detail of our precious concrete eaves. We had not ordered the siding yet, and so we could make the change to a stucco finish in a similar grey color to the waterproofing.

There were a number of other times where we looked at decisions we had made, and because we are ordering things as we go (admittedly not the most efficient method), we had the ability to make changes as a result of the way things look in the field. This is definitely the upside to being contractor, owner and architect all in one.

The house is not done yet (we hope early spring 2017 at the latest) but it has been a great learning experience that just keeps on giving. All of the finishing work is yet to be done inside, the stucco is not done and the solar panels are not installed. There are lots of things we would not do again, but most of them we do not regret, since we still think we will come out in a better place in the end. Stay tuned!